Description

The term “congenital hand difference” refers to any condition of the hand and arm that is present at birth. Children can be born with many types of hand differences and they vary greatly in their impact on the appearance and function of the hand.

Congenital hand differences develop early during pregnancy when the baby’s upper limbs are first forming. Sometimes, a difference runs in a family or is part of a medical condition but, in most cases, doctors are not able to determine the exact cause for a hand difference.

Having a hand difference can be both physically and emotionally challenging, but many children are able to adapt and function well without any treatment. Some children may need physical therapy, surgery, or other treatments to function better and be more independent.

AnatomyHello

Congenital hand differences can affect both the shape and function of a child’s hand and arm. They occur in about 20 out of every 10,000 babies born and are more common in boys than girls.

Hand differences are not usually detected before birth. Occasionally, a difference such as extra fingers or missing bones can be seen on a prenatal ultrasound, but this is rare.

Congenital hand differences are often divided into two categories:

- Malformations—in which a certain part of the hand or arm fails to develop normally while the baby is in utero, and

- Deformations—in which the hand and arm begin to develop normally but are prevented from doing so in some way

Malformations occur about 4 to 8 weeks after conception—when the baby’s upper limbs are first developing. Deformations can occur later in pregnancy.

CausehELLO

Sometimes, a congenital hand difference is associated with a medical condition or syndrome that affects multiple parts of the body. Hand differences may also be hereditary—they can be passed along through a family.

In the majority of cases, however, the cause for a hand difference is simply unknown—doctors are not able to determine why it has occurred.

Types of Hand Differences

There are many types of hand differences and the variance from a normal hand can be either major or minor. Some of the more common conditions are described below.

SyndactylyHel

Syndactyly, the most common congenital hand difference, is an abnormal connection of the fingers to one another. In babies born with syndactyly, the fingers are “webbed” or fused together because they did not separate normally during development.

The condition can take a number of forms, including the following:

- Simple syndactyly. In this form, the fingers are joined either by skin or other soft tissue, which may appear webbed. The webbing may be either:

- Complete—extending from the base of the finger all the way to the tip, or

- Incomplete—stopping at any point before the tip

- Complex syndactyly. In this form, the bones of the fingers are fused together. This form of syndactyly is more difficult to treat because, in addition to bone, the fingers may also share a nail, nerves, muscles, blood vessels, and tendons.

Syndactyly often runs in families and can occur alone or as part of a medical condition such as Apert syndrome or Poland syndrome.

Polydactylyh

Polydactyly is the presence of one or more extra fingers on the hand. An extra finger may be small and nonfunctional—made of only skin and soft tissue—or may be fully formed with bones of its own.

Most commonly, an extra finger is adjacent to the thumb or little finger. Rarely, an extra finger is between the other fingers.

Polydactyly often runs in families and is sometimes associated with other medical conditions or syndromes. In some cases, babies born with polydactyly will have syndactyly as well.

Limb Deficiencies

A baby with an upper limb deficiency may be born with hands or arms that are smaller than normal or are missing. Some of the more common limb deficiencies are described below:

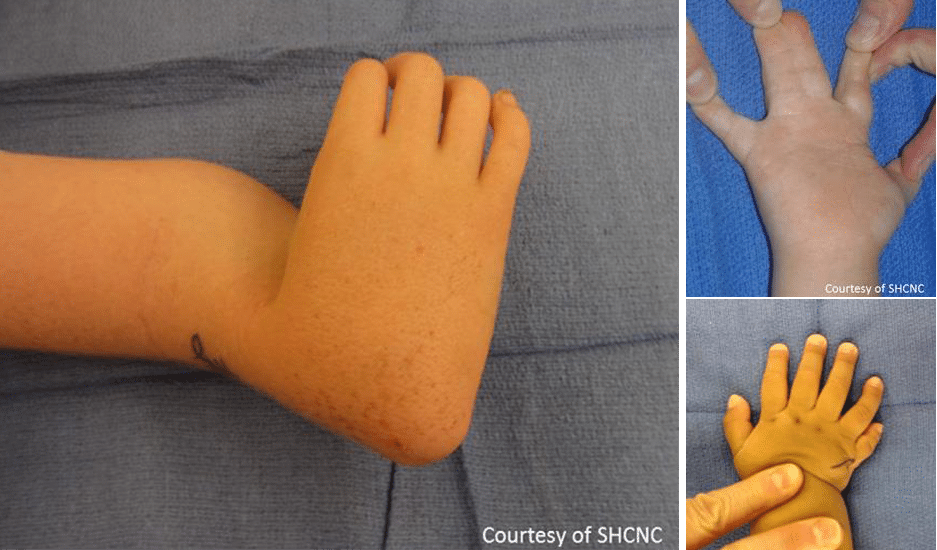

- Radial Deficiency : In a radial deficiency, the radius bone and soft tissues of the forearm fail to develop properly. This causes the affected hand to be bent inward toward the thumb side of the forearm, giving it the appearance of a “club hand.”

In a radial deficiency the hand is turned inward, giving it a club-like appearance.Courtesy of Shriners Hospital for Children—Northern California

The forearm may also be shortened and the thumb may be smaller and weaker than normal or missing—a condition known as “thumb hypoplasia.” Thumb hypoplasia may cause a child’s thumb to be missing or underdeveloped.

Thumb hypoplasia may cause a child’s thumb to be missing or underdeveloped.Courtesy of Shriners Hospital for Children—Northern California

Some types of radial deficiency run in families, while others are related to congenital differences in the heart, kidneys, and blood system. To determine whether a radial deficiency is caused by an underlying medical condition, your doctor may recommend a thorough evaluation by a pediatrician and/or a geneticist.

- Transverse Deficiency

In a transverse deficiency, all of the elements below a certain level in the patient’s arm are missing. The condition has an appearance similar to that of an amputation and is sometimes known as “congenital amputation.”

Doctors believe that a transverse deficiency occurs when a vascular problem, such as a blood clot in the limb, causes the affected arm to stop developing. The most common type of transverse deficiency is one in which the elements below the elbow are missing.

A child with a below-elbow deficiency, the most common type of transverse deficiency.Reproduced from Song K (ed): Orthopaedic Knowledge Update Pediatrics 4. Rosemont, IL. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 2011, p. 149.

A child with a below-elbow deficiency, the most common type of transverse deficiency.Reproduced from Song K (ed): Orthopaedic Knowledge Update Pediatrics 4. Rosemont, IL. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 2011, p. 149.

Amniotic Band Syndrome

The amnion is the membrane that surrounds and protects the developing baby. If the amnion ruptures or tears during pregnancy, it is possible for detached strands of the membrane to wrap around the growing baby’s body parts and cause injury—a condition known as amniotic band syndrome (ABS).

In milder cases, these strands, which are called “amniotic bands,” may cause only a minor groove or indentation in one of the baby’s fingers or limbs.

In the most serious cases, an amniotic band may be tight enough to restrict blood flow to the developing baby’s body parts. This can lead to the amputation of fingers or parts of the arm before the baby is born.

ABS is also sometimes known as early amnion rupture sequence (EARS), constriction band syndrome, or Streeter’s dysplasia.

Doctor Examination

Physical Examination

Most congenital hand differences can be detected soon after birth.

A pediatrician will perform a careful examination of your child’s hand and arm and, in most cases, will be able to diagnose the specific type of hand difference.

Some cases are more complex and have more than one feature, however, and referral to a specialist—such as a pediatric orthopaedic surgeon or pediatric hand surgeon—may be necessary to make the correct diagnosis.

Tests

Your doctor may order tests to confirm a diagnosis or to help plan your child’s treatment.

- X-rays: X-rays provides images of dense structures, such as bone. Your doctor may order x-rays to determine which bones in your child’s hands and arm are affected.

- Genetic testing: An evaluation by a genetic specialist may be recommended for children with certain hereditary hand differences or differences caused by medical conditions or syndromes.

- Additional tests: If the hand difference is associated with a medical condition or syndrome, your doctor may recommend additional tests to determine if other parts of your child’s body are affected, such as the heart or kidneys.

Treatment

The goal of treatment is to improve the function and appearance of the affected hand to the extent possible.

While some children are able to adapt to hand differences and function well without treatment, others may need therapy or surgery to be more independent and participate in the activities they are interested in.

Your doctor will consider many things when determining treatment, including the following:

- Your child’s age and overall health

- The type and extent of the condition

- The cause of the condition

- The needs and interests of your child and the goals of the family

- Your preference for a specific therapy or procedure

Nonsurgical Options

Nonsurgical treatment for hand differences often includes one or more of the following:

- Therapeutic recreation. Play, sports, and other activities can help build confidence and improve a child’s emotional well-being.

- Physical therapy. Specific exercises can strengthen the arm and hand and improve motion in the wrist and fingers.

- Occupational therapy. Exercise and training can prevent stiffness in the hand and improve handwriting and other skills necessary for daily activities.

- Assistive or adaptive devices. Using specialized devices can make eating, dressing and other daily activities easier.

- Prosthetics. Artificial devices can be used to replace missing parts or limbs.

Surgical Options

There are several surgical procedures used to treat congenital hand differences. The procedure your doctor recommends—as well as the age at which the procedure is performed—will depend upon your child’s specific condition and the type of surgery.

Surgical procedures for hand differences include:

- Separation of webbed or joined fingers

- Removal of extra fingers

- Reconstruction of fingers or other parts of the hand

- Skin grafts—to replace skin that is missing or has been removed as part of a surgical reconstruction.

Peer Support

Establishing peer contacts for both your child and your family is a very important part of treatment. Meeting other children with hand differences and their families will provide reassurance that you are not alone and can be an invaluable source of information and support.

You can find many support groups and discussion groups online. In addition, some children’s hospitals and other organizations sponsor “Hand Camps” for children with differences. These camps provide a safe and encouraging environment for children to socialize and participate in camp activities with other children who have congenital hand differences.

Long-Term Outcomes

Many research studies have shown that children with congenital hand differences have a very high quality of life. Although they may do some tasks differently, parents are often amazed at what their children can accomplish.

There is some evidence that having a more minor hand difference can actually have a greater psychological impact on a child than having a more significant difference. If your child is struggling with either the emotional or physical aspects of having a hand difference, it is important to be supportive and encouraging, and to share your concerns with your doctor.

Statistical data in this article was reviewed by the AAOS Department of Research and Scientific Affairs.